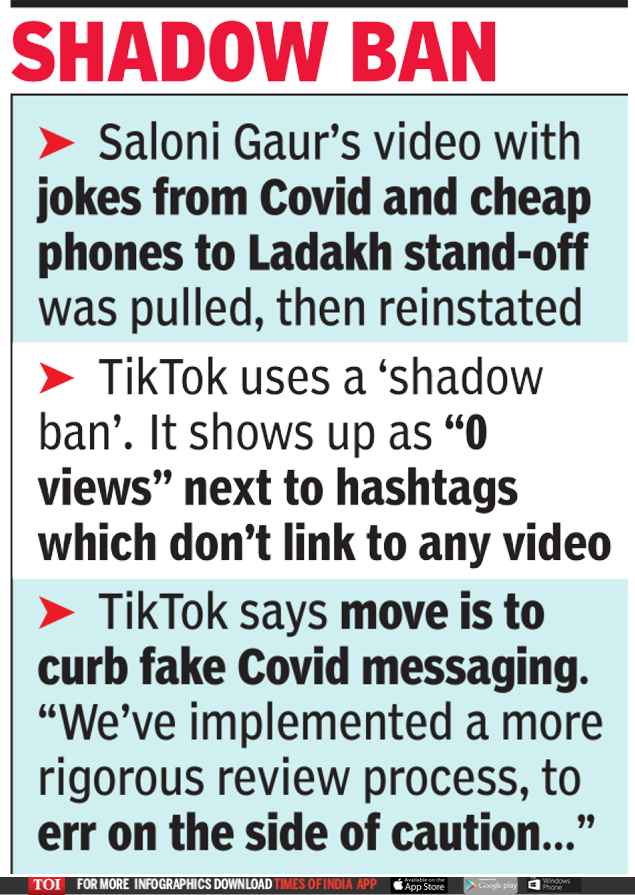

“So @TikTok IN has removed my last video which had jokes on China. Kuch bolne ki freedom hi nahi hai (There’s no freedom of speech),” Gaur tweeted. The video — in which she goes from “ajinamoto”, Covid and cheap phones to TikTok itself (“making us waste our youth”) and the Ladakh standoff (“I understand it’s a beautiful place, but leave now”) — was reinstated after her tweet. “There are videos on TikTok which show violence against women and animals and those are banned only when there is a lot of outrage. Mine was only making people laugh,” she told TOI.

TikTok attributed the whole thing to fake Covid messaging. “In context of Covid-19, we’ve implemented a more rigorous review process, to err on the side of caution and remove potentially violative content. The video in question was reinstated after being flagged and a further review,” a TikTok spokesperson told TOI.

India is TikTok’s largest base, with 36.7 million average monthly downloads, and 158.2 million monthly active users, 48.16% of whom open the app daily, according to app analytics platform SimilarWeb. So what does it mean for them?

TikTok has time and again faced the heat for what is called a “shadow ban”. A user who uploads the content is not notified but other users never get to see it because it does not come up on anyone’s feed. That shows up as “0 views” next to hashtags which exist but link to no video.

And it’s unpredictable. So #boycottchina had 1,45,500 views and #boycottchinaproduct had 1,21,500. But some disappear. The standoff along the India-China border at Ladakh, for instance, has spawned hundreds of videos on the platform. So while #ladakhchinaborder, #chinaladakh, #chinainladakh are all hashtags that exist, they have zero views and no link to the videos. In fact, that’s the same for several videos with hashtags mentioning seven strategic border points — Khunjerab (in Gilgit Baltistan), Chitkul (the “last” Indian village before the Tibet border), Wesh-Chaman (between Pakistan and Afghanistan), Sost (the first dry port on the China-Pakistan border), Wagah (India-Pakistan border), Sialkot (on the other side of the LOC with Pakistan) and Ramgarh (a border village in Jammu). Also out from Indian feeds is #tiananmenmassacre (though #tiananmen is up). And, strangely, #xijinpingismydaddy (the “Big Daddy” moniker for the Chinese president was hastily ditched by China after a quick assessment of its message in translation. The same had happened to #BlackLivesMatter and #GeorgeFloyd in the US recently, after which TikTok had apologised, attributed it to a glitch and reinstated the videos.

The TikTok spokesperson said the platform does not censor anti-China content. But in effect, such shadow bans are no different from censorship. A search on Baidu, the primary search engine in China, for “China Ladakh dispute”, “Ladakh China border”, “Ladakh dispute now” or even “where is Ladakh” throws up dated search results and a disclaimer that says some search results have been filtered — even when looked up from India. And while a search for “Ladakh China India” led to news reports that went back three to five years, about 35 minutes later, on hitting refresh, the search results were gone — all 3,67,000. “Sorry, no pages related to Ladakh China India were found.”

That brings up the other concern about apps based in China — how user-generated content from outside China is being used. In May, Canadian cybersecurity research unit, The Citizen Lab, had published a report documenting how WeChat was scanning images and files shared on the platform to train AI for censorship in China. “WeChat communications conducted entirely among non-China-registered accounts are subject to pervasive content surveillance that was previously thought to be exclusively reserved for China-registered accounts,” it said in its report. Which means messages exchanged by 7,91,928 Indians on WeChat, according to data from SimilarWeb, might be training machine learning models to censor political content in China.

Tencent, the Chinese multinational which owns WeChat, denied it. “We can confirm that all content shared among international users of WeChat is private … Our policies and procedures comply with all laws and regulations in each country in which we operate,” a Tencent spokesperson told TOI.

But these are grey areas. WeChat and Weixin, used in China, are subsidiaries of the same company. “We share your personal information within our group of companies,” WeChat’s privacy policy says.

TikTok’s privacy policy, likewise, says, “We may share your information with a parent, subsidiary, or other affiliate of our corporate group.” TikTok is owned by Beijing-based ByteDance, which also runs Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok. After security concerns flagged by several countries, ByteDance had said servers for the two apps are separate. Data from Indian users goes on servers in the US and Singapore. But TikTok can share user data with ByteDance subsidiaries, including Douyin. And Douyin does not operate by the same rules. Under 10 criteria for protecting China’s “national security”, Douyin’s privacy policy says, it “does not need authorisation to collect and use personal information.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment