index

Lack of sanitation awareness prevails at a greater extent here; it is unclear how COVID-19-centric awareness campaigns will influence behavioral change

When will this get over?

Science is still exploring a citable answer to this most frequently asked question across the globe. Available data and trends indicate that the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is not ephemeral and may stay among us until a sustainable weapon is made.

SARS CoV-2, the virus behind the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has now become a noxious global citizen, but carries unique problems and crisis for different geographies across the world.

Along with the known biological impacts of the disease, the virus carries multifarious strains which are impacting the population — socially as well as economically.

The urban sprawl

Urban transition started early in 19th century and by 2050 urban population will reach 70 per cent across the globe. While many developed countries already boast of being urbanised, the transition trajectory in India still shows steep upward and uneven growth.

Nearly half the India’s urban population is concentrated in states such as Maharashtra, Gujarat, Delhi, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Punjab and West Bengal. Economic and industrial growth in these states attracted skilled and non-skilled populace from states such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha and Jharkhand. However, the infrastructure of the receiving states was never meant to sustain this unprecedented load.

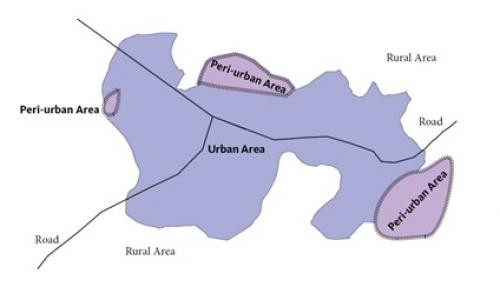

With existing load of intra-state rural-to-urban migration, this sprawling further created a concept of ‘peri-urban’ areas which are often marginalised from the formal urban settlement and a spill-over of urban population.

Peri-urban zones are primarily home to labourers and migrants, population of which was estimated to cross 100 million by 2016, according to a report submitted in 2010 by Pronab Sen committee constituted by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation.

Peri-urban Areas in a typical urban landscape

Vaccine, nutrition or sanitation?

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, the World Health Organization and Indian government mandated measures such as social distancing, frequent handwash and adoption of improved sanitation behavior for infection prevention and control. This appears to be an impossible feat in India where several slums like Dharavi struggle with population density of over 200,000 people per square kilometre and 63.1 per cent of slum population practices open defecation.

Communicable and infectious diseases, including respiratory infections, tend to spread at a faster pace into slums with high population density. With a limited access to sanitation and hygiene facilities, poorly maintained drainage and sewerages further exposes the risk of infection spread through human faeces and shared water resources at community stand posts.

Recent studies from Johns Hopkins University have not denied that SARS-CoV-2 is capable of becoming ‘aerosolised’ through untreated wastewater and exposed sewerages. During an empirical study conducted by the author at two urban slums resettlement colonies in Delhi — Holambi Kalan and Savda Ghewra in 2018 — it was observed that 35 per cent respondents used soil or ash to wash their hands after defecation.

Lack of basic sanitation awareness prevails at a greater extent in these settlements and it is unclear that how COVID-19-centric awareness campaigns will influence behavioral change among them.

The Union government is aware about loss of income during this abysmal crisis. When the inhabitants are struggling to get food and ration, it shouldn’t be expected from them to buy sanitisation products.

Office of principal scientific advisor K Vijay Raghavan issued fresh guidelines on April 13, 2020 to install foot-operated handwashing stations in densely populated areas and slums.

This is ironical — these noble measures are enabled when the crisis is already moderated. It wouldn’t be an easy task for the government to diffuse a sanitation innovation among a population, a majority of which is not even aware about the benefits of handwash.

High prevalence of malnutrition among children and elderly has already been the biggest concern in urban slums, with more than 60 per cent of children under five years of age malnourished.

Stressed financial situation and social isolation may severely impact their access to variety of food, thus increasing the chances of nutritional imbalance and expose them at risk of virus infection and as well as slowing down recovery.

In the best-case scenario, however, if scientists develop a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 and it is made accessible to slum residents, the risk will still persist. A study of Delhi’s urban slums has indicated that malnutrition and inadequate sanitary conditions will adversely impact effectiveness of a vaccine.

Can lockdown lock the virus?

Yes, within the community.

Though well-intentioned, unprecedented lockdown has upended the lives of slum dwellers in peri-urban communities with equanimity as most of them are solely dependent on the food and ration supplied by government and non-profits. This segment of population largely endures their livelihood with operating income and don’t possess cash liquidity to sustain such crises.

Isolating this population will majorly benefit other sections of the community by limiting the spread within a containment zone. However, the virus may keep multiplying within the community due to poor basic sanitary infrastructure, non-curated strategy of testing and monitoring, marginalised healthcare facilities and inadequate capacity building.

The reverse-migration predicament

Carrying a feeling of deep end of affairs, stigmatisation and impecunious with source to earn, the pandemic attained its zenith when thousands of migrants ambivalently opted to walk towards their far-flung homes due to non-availability of transport.

A few brave ones waited until they frantically rushed to Delhi-Ghaziabad border and Bandra railway station in Mumbai responding to various rumours — and a hope to reach their original habitat.

In the last week of April, the Union and state governments announced back-to-home travel guidelines for of migrant workers; Bihar alone estimated reverse movement of 28 lakh migrants.

Urban sprawling in India: Will COVID-19 trigger reverse-migration?

With a majority of migrant home states having poor public healthcare infrastructure and limited income generation opportunities, this plethora of reverse-migration may not only create a huge pool of suspected contagion in reverse-destination states, but also have a conflagrated socio-economic asymmetry at both origin and destination.

The COVID-19 pandemic not only opens research paradigms for scientists and healthcare professionals, but also an exigency for policymakers and government to reevaluate all primary and auxiliary policies, programmes which directly or indirectly impact life and livelihood of the population living in peri-urban areas.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

The post COVID-19 exposes fault lines in peri-urban areas appeared first on indifact .

https://ift.tt/36KCtLi

from WordPress https://ift.tt/36FDEvM

via IFTTT

0 Comments:

Post a Comment